A strange signal emerges from the Milky Way

The Galactic centre is usually the last place astronomers go looking for subtle physics. It’s a glare-filled knot of dead stars, hot gas and noisy radiation — a region where most delicate signals vanish into background chaos. So when a smooth, halo-like glow of 20-GeV gamma rays appeared in a fresh analysis of satellite data, it immediately stood out.

The signature comes from more than a decade of observations by NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. After accounting for known sources — pulsars, supernova remnants, cosmic-ray interactions and the blinding band of the Galactic plane — one component refused to disappear. And awkwardly for everyone involved, it looks remarkably like what dark-matter models have predicted for years.

A century-old mystery with a new lead

The idea of dark matter goes back to the early 20th century, when astronomers realised galaxies were rotating far faster than their visible mass allowed. Something unseen — and significantly heavier — was providing the missing gravity. Subsequent decades strengthened the case: gravitational lensing, cluster dynamics, cosmic-microwave-background maps, and simulations of large-scale structure all point to the same conclusion.

Yet every piece of that evidence has been gravitational. No one has ever observed dark matter interacting in any other way. That’s why a non-gravitational signature — especially in gamma rays — would be transformative.

A 20-GeV halo too clean to ignore

The new result comes from Tomonori Totani, who analysed Fermi data spanning roughly a hundred degrees around the Milky Way’s centre. His method was conservative: subtract foregrounds, model known processes, and see what remains.

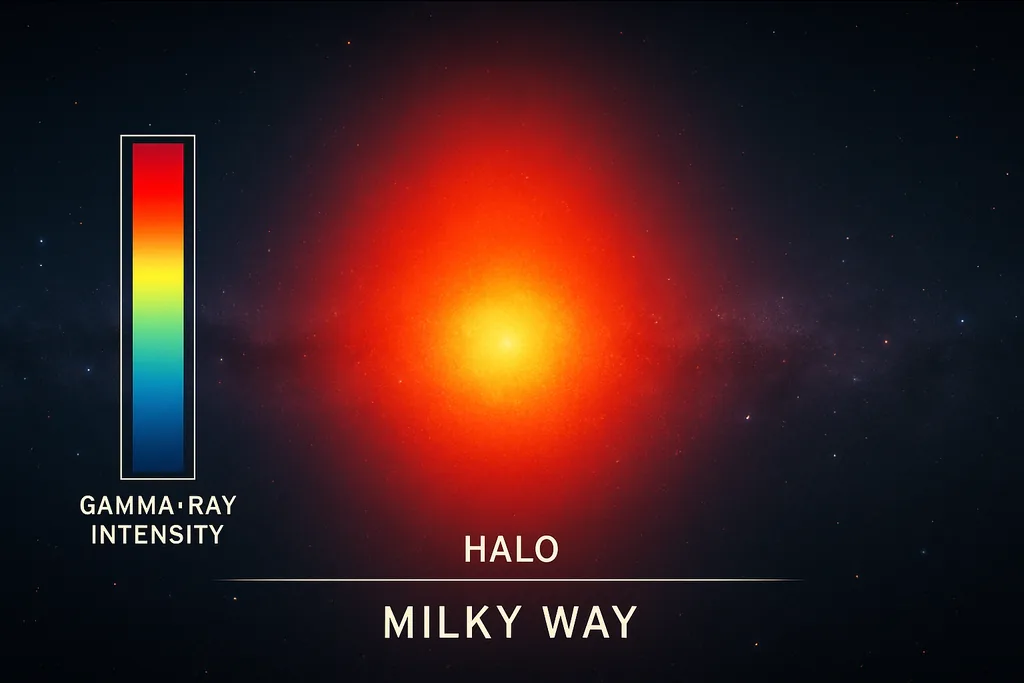

What remained was a broad, symmetric glow of high-energy photons, peaking at about 20 gigaelectronvolts — exactly where many dark-matter models predict emission from annihilating weakly interacting massive particles, or WIMPs.

The spatial pattern matters. This glow mirrors the expected shape of the Galaxy’s dark-matter halo: smooth, centre-focused, and extending far beyond regions dominated by ordinary astrophysical sources. Pulsars don’t produce that geometry. Gas interactions don’t spread that far. Supernova remnants aren’t that tidy.

It is, in other words, a pattern that shouldn’t be there unless something unusual is happening.

A particle that fits the models a little too well

The energy spectrum is what pushed the result from “interesting” to “difficult to dismiss”. The observed photons align closely with spectra produced when hypothetical WIMPs with masses around 500 times that of a proton annihilate into known particles like bottom quarks or W bosons.

Even the estimated annihilation rate — inferred from the brightness of the halo — sits comfortably inside theoretical predictions that have guided the field for years.

That consistency does not prove anything on its own, but it narrows the landscape. Known astrophysical processes struggle to reproduce the same combination of shape, energy peak and intensity.

Why caution still dominates

Dark-matter research has endured its share of excitement followed by disappointment. Seemingly promising signals — from the Galactic centre, dwarf galaxies or particle detectors — have withered under reanalysis, improved modeling or better data. This case could be another.

Totani stresses that the interpretation must be tested independently. Alternative foreground models might explain the glow. Instrumental effects must be ruled out. Even if the signal survives those filters, researchers will want to study similar environments where ordinary gamma-ray sources are scarce.

That points to dwarf galaxies orbiting the Milky Way — dark-matter-dominated systems with minimal astrophysical clutter. If they emit a matching 20-GeV fingerprint, the case would strengthen considerably.

A breakthrough, or the start of a sharper search

If the halo truly arises from dark-matter annihilation, it would mark the first detection of a particle beyond the standard model of physics and the most important cosmological discovery in decades.

If it turns out to be an unexplained astrophysical phenomenon, it will still refine models and sharpen future surveys. Either outcome advances the field.

For now, the gamma-ray halo sits in the uncomfortable space between intrigue and certainty — compelling enough to energise researchers, ambiguous enough to demand restraint. But after a century of chasing an invisible mass, even a provisional hint is enough to make the hunt feel newly alive.