Why this debate has flared up again

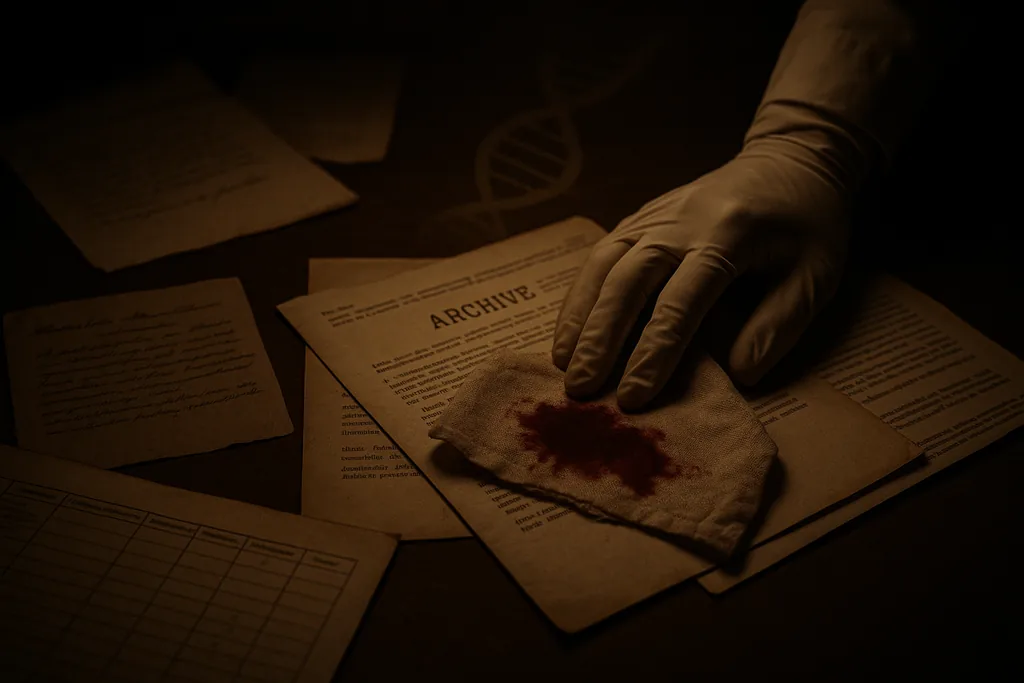

In November 2025 a television documentary returned the question of Adolf Hitler’s remains and genome to the headlines. The programme presented genetic analysis performed on a bloodstained fabric associated with the Führerbunker and claimed insights into ancestry, rare medical variants and even polygenic risk scores that were used to speculate about aspects of Hitler’s body and behaviour. The coverage revived older controversies — including disputed skull fragments kept in Russian archives, earlier DNA tests that produced conflicting results, and long-running rumours about Hitler’s health and origins.

What scientists actually analysed — and how

Reports around the new work describe a few separate elements: a fragment of skull and dental records historically retained in Soviet and later Russian custody; and a piece of textile reportedly stained with blood found on a couch recovered from the bunker area. Forensic teams inspected bone and tissue fragments, while geneticists attempted to extract nuclear and mitochondrial DNA from highly degraded material. One authentication route used in recent work was matching male-line Y-chromosome markers to living paternal-line relatives, a method that can tie degraded samples to a particular paternal lineage if a reliable modern relative can be found.

Those methods are technically feasible, but technically feasible is not the same as definitive. Old, burned, or heavily degraded remains present major hurdles: contamination from modern handling, chemical damage to DNA, and the difficulty of proving provenance for objects that passed through many hands in the chaos of wartime Berlin and subsequent decades of custody.

What DNA can — and cannot — tell us

Genetics excels at some kinds of questions. Mitochondrial DNA or Y-chromosome markers can help confirm maternal or paternal links. Rare pathogenic variants can indicate a higher probability of certain medical conditions. Ancestry-informative markers can place a genome within broad population-level patterns, and modern forensic methods can sometimes narrow down age-at-death or biological sex from skeletal remains.

But the limits are equally important. Genetic data rarely provide deterministic explanations for complex traits such as behaviour, decision-making or ideology. Polygenic risk scores (PRS), which aggregate small effects across many genomic locations, are population tools — useful for research and probabilistic risk on groups, much less reliable for diagnosing or describing a single historical individual. Using PRS to make claims about a person’s psychology or propensity for violence crosses from genetics into speculation.

Scientific value versus sensationalism

Proponents of studying high-profile historical genomes argue the science can settle long-standing questions: was a particular skull fragment really from the person in question? Did a leader have a genetic disorder that might explain certain health records? Can ancestry testing refute persistent myths? These are legitimate historical and forensic aims.

But media narratives often strain beyond those aims. Focusing on lurid personal details — genitalia, rumours of single testicle, or a genetic ‘blueprint’ for criminality — risks transforming careful laboratory work into spectacle. That spectacle can obscure rigorous caveats and encourage misinterpretation in the public sphere.

Ethics: consent, precedent and the victims

Unlike living research participants, historical figures cannot consent. That raises unavoidable ethical questions. What responsibilities do scientists and broadcasters have when studying the remains of notorious people? Different actors — museums, archives, national governments and scientific journals — have developed guidelines for handling remains and human tissue, but there is no international consensus that neatly governs the dead in the way modern medical ethics governs living participants.

There are also victims to consider. Research that humanises, mythologises, or medically pathologises perpetrators can have consequences for survivors and their descendants. It may detract attention from the historical record of responsibility and the social and political conditions that enabled atrocities. Worse, genetic explanations for behaviour have a fraught history — especially when they echo the rhetoric once used by the Nazis themselves to justify eugenics and exclusion.

Legal and custodial questions

Guidelines for responsible historical genomics

- Clear, limited research questions: Tests should be designed to answer specific forensic or historical questions rather than broad behavioural hypotheses.

- Robust authentication: Multiple lines of evidence — laboratory controls, replication in independent labs, and secure chain of custody — are essential.

- Independent oversight: Institutional review, involvement of ethicists and historians, and engagement with affected communities reduce risks of misuse.

- Careful communication: Results must be framed with scientific limits clearly explained; sensational claims should be avoided.

- Contextualisation: Genetic data should be integrated with documentary, forensic and archival evidence, not presented as standalone proof of motives or personality.

So, should Hitler’s DNA have been studied?

There is no simple yes-or-no answer. Some lines of enquiry — for example, authenticating a disputed bone fragment or confirming the provenance of wartime material — are legitimate forensic projects that can add clarity to the historical record. Other pursuits, particularly those that infer personality or moral culpability from genomic data, are scientifically weak and ethically fraught.

The responsible path is one of restraint: testing when the goal is precise and verifiable, doing so with transparent methods and independent oversight, and resisting the temptation to convert genetics into a salve for complex historical questions. The public interest in the life and death of infamous figures is understandable, but harnessing modern genetics to feed sensational narratives risks doing real harm — to science, to public understanding, and to the memory of victims.

Why the conversation matters

This debate is about more than one historical corpse. It sits at the intersection of emerging genomic power, media incentives, and the fragile ethics that govern work on the dead. How we choose to use genetic tools to probe the past will set precedents for museums, courts and historians for decades to come. Thoughtful, cautious practice can yield useful facts without surrendering nuance; uncritical excavation for headlines will do neither the science nor the public any favours.

— Mattias Risberg, Dark Matter. I report on science, space policy and data-driven investigations from Cologne.