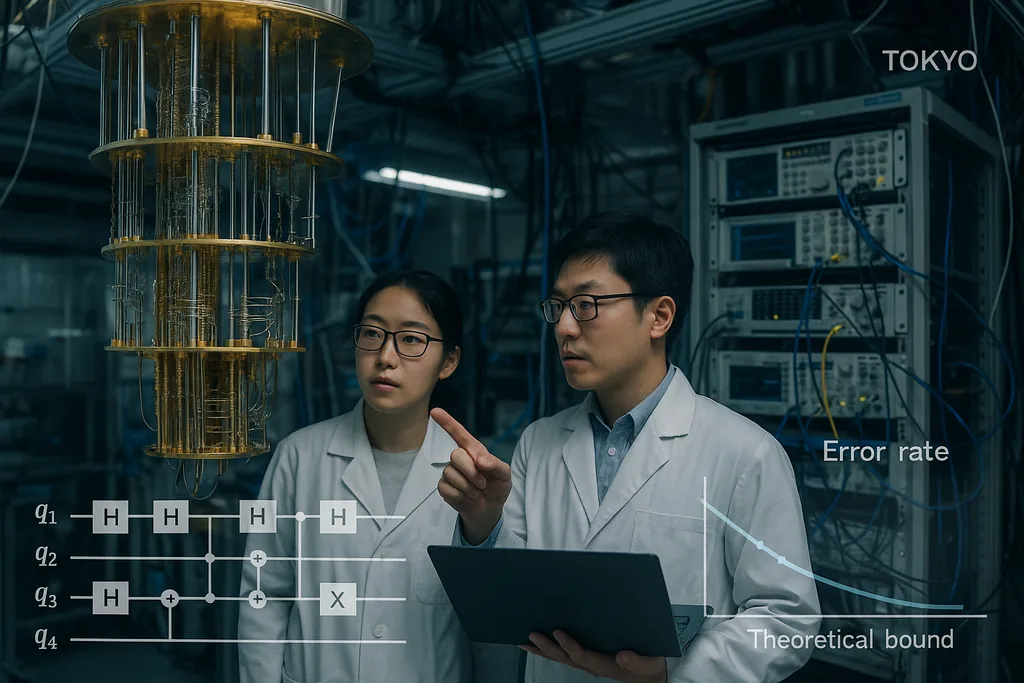

New codes cut the noise that keeps quantum computers from scaling

On 30 September 2025 a team in Tokyo published a paper showing quantum error‑correcting codes that come unusually close to the long‑standing theoretical limit for reliable quantum communication and computation — the so‑called hashing bound — while remaining efficiently decodable. The result, now highlighted in institutional write‑ups, is not a one‑line magic fix; it is a careful redesign of low‑density parity‑check constructions and their decoders that together push frame error rates down to practical levels and keep computational overhead low. Those two features — near‑capacity performance and decoding cost that scales linearly with the machine — are the very properties needed to move quantum processors from laboratory curiosities to machines that can tackle real problems in chemistry, cryptography and climate science.

A near‑capacity code for the noisy quantum channel

The hashing bound is an information‑theoretic ceiling: it marks the highest rate at which quantum information can be transmitted reliably across a noisy channel when using optimal coding and decoding. Historically, quantum codes that are provably efficient have been far from that limit or required impractically heavy decoders. By demonstrating codes that both approach the bound and can be decoded with classical resources that scale modestly, Komoto and Kasai make a persuasive case that hardware scaling — the project of wiring up millions of physical qubits to yield many logical qubits — is a realistic engineering target rather than a theoretical pipe dream.

Decoders: the unsung bottleneck becoming a solved problem

Error‑correcting codes are only half the story; fast, accurate decoders are the other half. Over the past year several algorithmic advances have chipped away at the decoding bottleneck. In June 2025 researchers described PLANAR, an exact decoding algorithm for certain code topologies that turns a seemingly intractable maximum‑likelihood decoding problem into an efficiently solvable spin‑glass partition‑function calculation on planar graphs. When applied to experimental data, PLANAR reduced logical error rates significantly and showed that part of what looked like hardware limits was actually a suboptimal decoder. That insight matters because it means better decoders can extract more performance out of existing devices without any change to the quantum hardware.

At the engineering end, industry teams are moving these decoding ideas into real‑time classical hardware. IBM recently reported that a key error‑correction algorithm can run on conventional AMD FPGAs fast enough for real‑time feedback in superconducting systems, demonstrating operation well beyond the speed needed for many architectures. Running decoders on accessible classical chips is a crucial step: it transforms error correction from an offline, costly software process into a practical, low‑latency service that can be embedded into control stacks for large machines. Together with the near‑capacity codes, fast hardware decoders close the loop between theory and deployable systems.

What this convergence means for real applications

Quantum applications that promise transformative value — molecular simulation for drug discovery, optimization for logistics, or new cryptographic primitives — typically require millions of logical qubits or extremely low logical error rates sustained over long computations. Until now those resource estimates translated into astronomical counts of physical qubits because error correction had both poor thresholds and costly decoders. The combination of Komoto and Kasai's coding constructions, improved decoders such as PLANAR, and the push to run decoding on standard classical hardware substantially lowers that overhead in principle. That shifts the balance: a generation of quantum hardware that was previously judged impractical may now be within reach if engineering teams can deliver moderate‑scale qubit arrays with the expected physical fidelities.

There are already application‑oriented threads building on this work. For example, researchers exploring quantum machine learning have shown that partial or approximate error correction can make near‑term quantum models far more practical than before, reducing the hardware demands needed to see an advantage. Such synergies between coding theory, approximate fault‑tolerance and algorithm design could accelerate practical uses on intermediate machines even before full fault tolerance arrives.

Barriers that remain

Despite the progress, several hard engineering and physics problems remain. The codes and decoders in the Komoto–Kasai paper are demonstrated in simulations and numerical studies; moving them into silicon, superconducting circuits, trapped ions or photonic setups requires engineering decoder pipelines with extreme real‑time guarantees, routing millions of signals through cryogenic stacks, and suppressing rare but devastating effects such as cosmic‑ray induced correlated errors. Implementing non‑binary finite‑field arithmetic in hardware, integrating syndrome extraction without adding noise, and validating performance in realistic device noise models are nontrivial tasks that will determine whether the numerical promise becomes an operational reality.

There are also competing hardware strategies at play. Some groups are improving the hardware's intrinsic error resilience — for example, photonic and cat‑qubit approaches claim different tradeoffs between natural noise biases and resource counts — and benchmarking between these architectures will be essential as scalable decoders become available. Not every architecture will be able to exploit every code or decoder equally well, so the community still needs cross‑platform validation.

From theory to engineering: the next steps

The path forward looks like a coordinated three‑track programme. First, code designers will refine constructions to handle more realistic noise models and correlated errors, and to lower error floors further. Second, decoder teams will continue to reduce latency and energy cost and to port algorithms to FPGAs, ASICs and cryogenic logic where necessary. Third, hardware groups will benchmark codes and decoders on real devices, reporting not only logical error rates but also the hidden infrastructure costs: classical compute, wiring, cooling and maintenance. If those three tracks converge, the community will be able to turn the abstract promise of quantum advantage into concrete roadmaps for machines that do useful work.

In short, the recent work on near‑hashing‑bound LDPC codes is not an isolated triumph but the latest, convincing sign that a combination of smarter codes, better decoders and practical classical hardware integration can close the gap between theory and application. The timeline for broadly useful quantum computing remains uncertain, but these advances materially improve the engineering case for building the next generation of machines that will try to do real work for industry and science.

Sources

- npj Quantum Information (Komoto & Kasai: "Quantum error correction near the coding theoretical bound").

- Physical Review Letters (Cao et al.: "Exact Decoding of Quantum Error‑Correcting Codes").

- Institute of Science Tokyo press materials summarising the Komoto & Kasai work.

- IBM research disclosures and reporting on FPGA implementations of quantum decoders.