Aguada Fénix: a landscape turned into a map of the cosmos

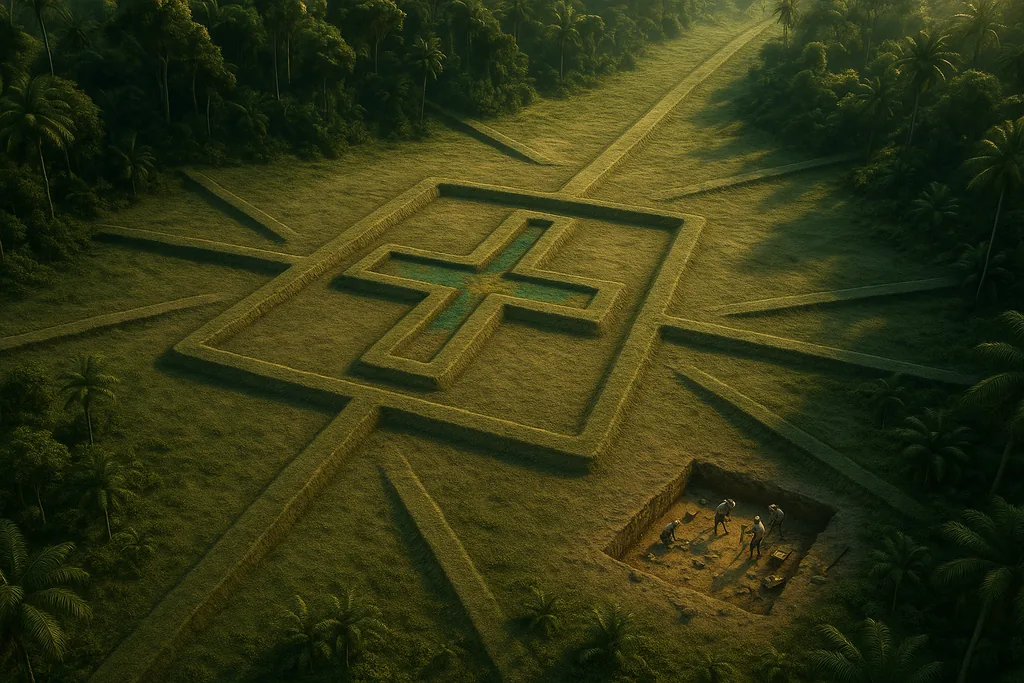

Archaeologists working in the lowlands of Tabasco, Mexico have reinterpreted one of the largest and oldest known Maya monuments as a deliberate, landscape‑scale cosmogram — an architectural map expressing how people organised space, time and ritual three millennia ago. The new analysis, based on field excavations and airborne laser mapping, argues that nested cross forms, colour‑coded caches and an extensive hydraulic network together encoded cardinal directions, calendar intervals and water symbolism in physical form.

How a flat platform became visible

The cruciform cache: colour, direction and ritual

At the heart of the interpretation is a cruciform (cross‑shaped) pit the team excavated inside an architectural complex known as an "E group" — a form previously associated with solar observations. Beneath later fills the researchers found a smaller, nested cruciform containing carefully placed piles of mineral pigments and marine shells. The pigments line up with cardinal directions: vivid blue azurite to the north, green malachite to the east, yellow ochre to the south, and seashells and faded red traces to the west. The arrangement matches long‑standing Mesoamerican symbolic associations between colours, directions and sacred meaning, but this is the earliest physical instance yet found of pigments placed precisely to mark direction.

Canals, dams and a cosmological grid

Beyond the cruciform, the landscape contains long canals — some up to 35 metres wide and several metres deep — plus a dam that linked the ritual complex to a lagoon. When seen from the air, the canals, causeways and platforms form nested cross‑patterns extending across kilometres and aligning with specific sunrise dates that bracket a 130‑day interval, which the researchers link to half of the 260‑day ritual calendar used later across Mesoamerica. That alignment, and the sheer scale of earthworks involved, are central to the claim that the layout functioned as a cosmogram: the community literally translated cosmic order into engineered terrain.

Big builds without big bosses?

One provocative implication of the new study is social. Unlike later Maya capitals, excavations at Aguada Fénix have so far revealed no palatial compounds or monumental elite tombs that signal centralized, coercive leadership. The authors propose that the monument was planned and built through concerted communal effort — organised by specialists who knew the calendar and the sky, rather than by an authoritarian ruler. In this view, large ritual construction could be an expression of cooperative identity rather than a direct instrument of elite power.

Objects that hint at meaning

The assemblage recovered from the cruciform and nearby deposits adds texture to that picture. Researchers recovered jade ornaments and clay objects shaped like animals, and — intriguingly — a carved piece interpreted by the team as representing a woman in childbirth. Some offerings appear to have been left at different moments in time, suggesting the place stayed ritually significant long after the original filling of the cache. Together, those finds point to a ritual vocabulary focused on natural life cycles, water and directional cosmology rather than the iconography of kingship familiar from later Maya art.

Why this matters for how we see early Mesoamerica

If the cosmogram reading holds, Aguada Fénix changes two standard narratives at once: it pushes back the timeline for large‑scale monumentality in the Maya area and shows that complex, territory‑spanning constructions need not imply the same kinds of political hierarchy archaeologists see at later sites. The discovery supports an emerging view in archaeology that ritual, feasting and shared calendrical knowledge provided powerful incentives for collective labour, creating monumental landscapes without the machinery of empire.

Points of caution and next steps

Not everyone takes the cosmogram label at face value. Some specialists urge restraint: "cosmogram" can be a broad term, and questions remain about whether every arranged axis and cache must be read as an explicit map of the universe or whether practical reasons — drainage, social gathering, seasonal movement — also shaped the plan. Additional excavation, more fine‑grained dating and comparative work at neighbouring sites will be needed to test which features were symbolic, which were practical, and how both categories overlapped in practice. The discovery opens new avenues for fieldwork, but it does not yet close the debate.

What archaeologists will do next

The team plans continued excavation and broader regional surveys to place Aguada Fénix in its landscape of nearly 500 smaller ceremonial complexes that recent studies have identified nearby. Future work will refine the chronology, expand the sample of ritual deposits, and investigate how water management, movement across the site, and periodic gatherings were coordinated. Because the site predates written inscriptions in the Maya area, the material layout itself becomes a rare, direct source for how people organised ideas about the sky, the calendar and communal life.

Conclusion: a map you can walk across

Aguada Fénix presents a striking image: an inhabitable map on which people could meet, observe the heavens and reaffirm shared timekeeping and ritual practice. Whether one calls it a cosmogram, a ceremonial landscape, or a huge communal plaza, the site's combination of pigments, pits, canals and alignments rewrites part of the story about how large‑scale architecture and social organisation developed in early Mesoamerica. As excavations continue, the monument will help historians and archaeologists test new ideas about cooperation, ritual knowledge and the material expression of cosmologies long before monuments we usually think of as "classical" Maya appeared.

Mattias Risberg is a Cologne‑based science and technology reporter for Dark Matter. He holds an MSc in Physics and a BSc in Computer Science from Universität zu Köln, and covers archaeological science, space policy and data‑driven investigations.